Nari Ward with Nicole Smythe-Johnson

Nicole Smythe-Johnson

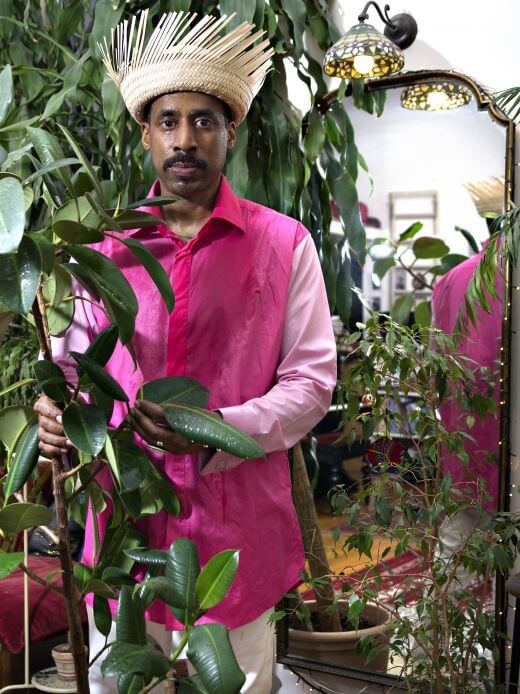

Nari Ward, Sun Splashed, Artin, 2013. Chromogenic print, 99 x 73.6 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Continua

Nari Ward, Savior, 1996. Plastic garbage bags, cloth, bottles, shopping cart, metal fence, earth, wheel, mirror, chair, and clocks, 325.1 x 91.4 x 58.4 cm. Installation view: Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, Kansas. Image courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, and Hong Kong

NICOLE SMYTHE-JOHNSON (MIAMI RAIL): How would you describe your practice?

NARI WARD: My biggest challenge in being an artist is to reach and understand who my audience is. To understand why certain individuals that you may not think of as part of your audience may be interested in your work. How to find a way to speak to the person who has no interest in contemporary art, as well as the person indoctrinated in the ideologies of contemporary art. Bridging that space is what I’m really challenged by. How to work with material that can trigger interest, but then layer the possibilities within the object or material I’m working with.

And the use of craft, or some interest in how something’s made, what material processes apply to it, is all about trying to negotiate that dialogue between the person who needs to see the land and the labor, and the one who might have a more conceptual expectation.

RAIL: Why use found objects?

WARD: The viewer (whoever they are, wherever they are in society), they’ve already had some experience with the object and so it’s hijacking that, to take it somewhere unexpected for them, and maybe transform this thing into something symbolic, or even something intimate.

RAIL: So, you’re thinking about these materials as a means of seduction.

WARD: Yes, because that person has seen this thing before, and so they have a set of expectations for it based on their memory. It’s really about trying to deal with those expectations, then insert other possible readings for the work or the object. All this is about using the familiar to point to a space of awakening. Because it’s really about the unknown. You try to do these strange conflations that somehow will lead somebody inward, into thinking about some aspect of themselves. The self is always this very shady space, right? Because there’s a certain amount of knowing oneself and then there’s a lot of the unknown within that knowing. This is what psychologists are always trying to mine. I think trying to have people look inward is a very rich space to investigate.

RAIL: And it initiates a way of looking that can be applied generally, as well. If you start looking at objects and thinking about what they mean in broader ways, then it’s possible to turn that eye on anything, even things that are not identified as artwork per se.

WARD: Exactly. I think that’s kind of what all these artists, from [Andy] Warhol to [Joseph] Beuys—I’m not trying to over-simplify it—but it’s this idea that we’re all artists. Not that we all make things, but we all have the ability to ponder critically. I think that level of thought and actualization can be meaningful in lots of ways—in a social justice way, and it’s such a relevant time to address things of that nature, even in the contemporary art world. And then also just aesthetics, and the joy of looking at something. For me, it’s about finding a way to negotiate between those realities: the luxury of looking and the need to have a kind of activist mode within the thought process of the work.

RAIL: There are social justice considerations running throughout your work. Is that deliberate? Is it based in a general feeling about how art should exist in society? Or is it more specific?

WARD: You know, you start with things that you question, right? So I’m always wondering: Why? Why are things the way they are? How can this material, that we all know as this specific thing, lead into these other sets of questions that might be about inequality, or police aggression, or the abuse of authority? All of these are things that I’m affected by and worry about. I also think about color and material, and the beauty of material. My thing is not creating a hierarchy for them to exist. I just put them together and see what they become. If you want to talk about abuse, and you want to talk about the color blue, how do you bridge those two choices? And the decisions you make to bridge those two choices are going to affect what you started with. You can’t start with a palette of colors and then get to talking about social justice if you don’t already have that question, and vice versa.

I live in the art world. There’s a certain. . . I don’t want to say luxury, but privilege in it. Then I walk the streets of my neighborhood, and I see certain abuses and injustices that I want to negotiate and talk about, and give or find a perspective on. It’s a very personal engagement that I try to make accessible to somebody who doesn’t necessarily know about these personal engagements. Yet they can still have a dialogue with the work based on their own experiences.

RAIL: Your neighborhood is very significant to your practice.

WARD: Yes. I live in Harlem. I’ve been living there now since ’85. The middle of the ’90s was the worst time for Harlem, with crack and AIDS and just urban blight. And now we’re seeing a very different moment in the life cycle, with gentrification and this change that is good and bad. But it’s also a very interesting trajectory for a black neighborhood. They call it “Harlem, the big mango,” so it’s more this African diasporic neighborhood that is going through a sort of self-actualization, deciding what it needs to be, evolving. There’s no easy solution. The gentrification is good because it raises the tax base and services increase in the neighborhood; you can hire more police, have better restaurants. But then there are the bad things, like the middle and lower income people getting pushed out of the neighborhood because they can’t afford to live there anymore. It really is this very strange monster to try to feed, and do that in a moral way.

RAIL: I guess it’s a similar process to asking people to engage with the found objects you work with in new ways, and in so doing, initiating this creative moment in thought.

WARD: Right, and question what and how they think about something. Even question the apparatus for thinking, and even me: Who is this artist? What’s he doing? What’s he thinking about? I feel like digging deeper and not taking things at face value is really important for anybody’s awareness, not just self-awareness, but awareness about how the media plays with you, family members, friends. How you’re being manipulated. I think questioning things is a very necessary survival mechanism.

Nari Ward, Radha LiquorsouL, 2010. Metal and neon sign, PVC tube with artificial flowers, shoelaces, and shoe tips, 320 x 63.5 x 73.6 cm. Collection of Rachel and Jean-Pierre

Lehmann

RAIL: It’s also a different way of thinking about empowerment, because the ability to analyze, to question your own ideas and question how you’re being manipulated is this ephemeral form of empowerment, a kind you can utilize without a weapon.

WARD: Right, right. We do this in academia maybe more often than we should, but it’s this Socratic process of looking and contemplating and everybody talking about what their read is on something and learning from these different voices. It’s really something that doesn’t happen enough in contemporary society. You see it happening on the street, this is how you get folklore coming up, and that, for me, is also really interesting. How things translate in popular culture and on the grassroots level. I think it was Spike Lee who did this documentary on Katrina [When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts, 2006], but what I was fascinated with is how he mixed the authority of the voices of the politicians, the historians, the social scientists, and the guys on the street. He got all their reads on what happened in the breakdown of the powers that be to handle that catastrophe. I thought it was very strange—the read from the street versus the authoritative dialogue, but then I realized that the combination of the two was the reality somehow. And it wasn’t a pure reality, but somewhere in this murky space where reality doesn’t become comfortable, but isn’t science.

Nari Ward, Mango Tourist, 2011. Foam, battery canisters, Sprague Electric Company resistors and capacitors, and mango seeds, 3 figures, 304.8 x 182.9 x 182.9 cm each. In collaboration with MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

RAIL: This contrast between embodied experience and conceptual experience— the information that’s generated by the powers that be—I think there’s an interesting parallel there in what you’re talking about with material. As an artist, you have this engagement with the material in its and innovation, because the balance isn’t necessarily fifty-fifty, it could be seventy-thirty. It’s all about trying to have it all there, but the metering of it is always very unexpected for me.

RAIL: Your work is often read through the lens of your Jamaican origins, is that how you see it?

WARD: I’m very uncomfortable with being called a Jamaican artist, because I left there quite young. I go back periodically. And when I go back, it’s always inspiring because it triggers memories and ways of working with material that are quite unique. I’m inspired by that. But I can’t say I’m a Jamaican artist, because I see the artists in Jamaica who are there working on a regular basis. And when I go to Europe, it’s funny, because they see me as an American artist. So these labels are malleable, according to what people expect. I don’t invest a lot in them. When I talk about the work, it’s really about me evolving as a person, and part of that evolution is thinking back on the memories of Jamaica.

I also realize that those memories are not real. The older I get, the more they become almost sugar-coated. I had all these memories of the house I grew up in, and I had a chance to go back to the house. This was after fifteen, maybe twenty years. I was shocked. I was, like, “this place is a dump, and so small.” In my memory, it felt so special and grandiose. So it’s a very strange realization, the reality of what was. I almost wish I didn’t go back, because it kind of shook me, you know? It shook my sense of self in a strange way. At the same time, at least two or three bodies of ideas have come about from my recalculating that reality. So I do feel like that experience of Jamaica is a part of me, but it’s not one I’m comfortable with using to say “I’m a Jamaican artist.” I’m an artist who references Jamaica, because it’s a very important place in my memory, and my development as a person.

RAIL: It connects with your general approach, working with objects from neighborhoods that are familiar to you. I guess, Jamaica is one of those neighborhoods, as much as Harlem is.

WARD: But even more special because it’s a neighborhood I don’t have access to. I’ve become alienated from it, so it’s that much more patina-ed with a kind of richness. Now it’s in a very special space—you can’t really access that space anymore, but it grows as you move away from it. It grows in a different way, you know? So the fiction of Jamaica, the fiction of being a Jamaican artist is probably what appeals to me more, because within that fiction is some element of reality.

I remember, I was there once doing a project at the National Gallery of Jamaica. That was Curator’s Eye and Lowery Stokes Sims had invited me. It was the first time I went to do a show there. There was this young lady who was helping me, she was volunteering. And she says, “Mr. Ward, I’m an artist here in Jamaica, I just graduated. And I want to know what you think I should do to be successful.” I had a lot of guilt for this, but my first words for her were: “Get out.” I was just being very straightforward. A couple of days later I was thinking about it, and I thought: “Maybe that was a bad thing to say to her, maybe she can’t get out.” But I didn’t know what else to tell her, because I didn’t build my career in Jamaica. I was just drawing on what I needed to do. I ended up being in touch with her, we were in a show together in Connecticut. She’s doing quite well now, she got out. It was Ebony Patterson. She’s teaching in Kentucky. So that was great. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to be an artist in Jamaica, and I think it’s because there’s no support in place for artists. There’s support for craft, but not for artists who are questioning everything.

RAIL: Yes, I know Ebony. She’s in Jamaica quite often, sometimes for several months at a time. I think lots of Jamaican artists are trying to negotiate wanting to be in Jamaica, but not having enough support

to make their work here, particularly if they’re interested in more challenging interrogations. You lived in the United States for a long time before you decided to pursue American citizenship. At least two decades, right?

WARD: What’s interesting about going through the process of becoming a US citizen, I thought I would just blow through this ceremony. But it was actually very powerful, I was really impressed with how it affected me. I didn’t think it would have much effect, but they swear you in with a hundred and something people, and you see people crying, it was a really powerful moment. I couldn’t help but share this sense of gratitude about doing it.

RAIL: Quite a bit of work came out of that for you, as well.

WARD: Yes, everything affects the choices you make. And much more being an artist, it manifests itself in the material questions, comes through the material. Liberties and Orders [2012] came around that time. That was three or four years ago, at my gallery Lehmann Maupin in New York.

RAIL: I was looking at that work, and I had to go back and look at the date. With everything that’s been happening over the last year with police brutality, it feels like a work that could have been made last month.

WARD: Right, it was precursor to all of that. And that show was well regarded when I did it, but the people who really got involved were the ACLU folks. They came and had me speak to several students. It was real interesting, because I don’t really see myself as this kind of activist artist, but the questions being generated, because I was seeing the changes in the neighborhood, because of the policing policies that have now came to a head. But I was just trying to deal with the neighborhood.

I know the art audience, including my gallery, didn’t really know what to do with the work. I did about thirteen pieces, and they sold absolutely nothing in the show. And it’s only now that people are coming back, and asking, “Is that work still available?” It’s very strange to see that happen, because it made me realize—I already knew it, but it reaffirmed the notion—that being successful has nothing to do with sales. I think that, even to date, it was one of my strongest shows because it was so important to do. And it was also one of my biggest financial bombs, because it was so important to do. So it was this very strange break in the market and this notion of what’s important.

RAIL: In Canned Smiles (2013), you made two cans—“Black Smiles” and “Jamaican Smiles.” Having gone to school in the United States myself, this really tapped into the tension I felt being a foreign black person in America, my relationship to African Americans, and the history of race in the United States. I wonder if it comes from a similar place for you?

WARD: I’m glad you triggered that, because that was one of the elements. There are a bunch of elements in that piece that I wanted to engage. It was this idea of relating the African American minstrel character with the kind of happy Jamaican mento singer.

RAIL: “Jamaica, no problem,” and all that.

WARD: Right. And one of the triggers of that was my time in Rome, because I was thinking about [Piero] Manzoni’s shit cans, and the way he talked about addressing notions of value. It was more financial value, because his cans, if there was shit in them, were priced by weight and the value was correlated to the price of gold. So it was about the notion of value as it relates to art practice. Manzoni is one of my favorite artists, so I wanted to reference him. But I wanted to take it in a different direction and have this value element be more about faith— the faith in what’s inside. The cans all have mirrors inside, and then people smile into the cans. So I smile, my family smiled, and then we close it immediately. In theory, the smile is there, but the smile isn’t there if you open it. So you had to believe for it to really resonate. I’m really excited about the work existing on that kind of plane as well.

RAIL: Thinking about a place like Jamaica, and minstrelsy, these smiles are heavy.

WARD: But the other thing is not to victimize these individuals, because they’re not victims, they’re survivors. The smile was resilience, the smile was fortifying yourself, and going out there and making money for your family.

RAIL: We always want to have this very neat line between accommodation and resistance, but it’s never that simple, is it? You did a later version of that project in Harlem, where you were selling the cans for $10 and contributing to a building project.

WARD: The building was actually the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling, and the organization that built the building, the Broadway Housing Communities, they do low-income housing. Part of their mandate is to have an art-education program for young children living in the low-income housing. I think it’s a great idea, incorporating visual art as a way to have them become critical at a very young age. Supporting the program within the new facility was what the cans were sold for. It’s the idea that smiles collected from the neighborhood will now benefit the young people who are going to be, hopefully, contributing to the neighborhood.

RAIL: And again, inscribing those smiles with agency, because you give up a smile and you get this great program for your neighborhood. Which gives it a different tone—not a situation of victimhood.

WARD: Yeah, for me that was the important thing. In all the work, I never wanted to get stuck in this kind of poverty tourism. It’s really trying to figure out how to give another position on one reality, because there are so many different ways to see something. To have that become as apparent to the viewer as possible. I think that’s why I gravitated toward the ambiguity of contemporary art, because it allows the viewer to finish the sentence.

RAIL: There are also these snowmen that keep recurring in your work. I’ve seen them in Blacktop Man [2006], Sub Mirage Lignum [2011], Sweet Sweat [2006], and Mango Tourists [2011]. What’s the snowman about?

/text]

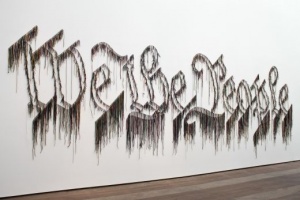

Nari Ward, We the People, 2011. Shoelaces, 243.8 x 823 cm. In collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

WARD: [Laughs.] I thought it was a great form to complicate the island narrative. It was my pushback against this “Jamaican artist.” In a strange way, that snowman became this vehicle for content that would be unexpected. At the same time, it was this memory piece for me. When my mom was trying to get us to the United States, she would talk about the winters, and ice in the street. You can imagine for a young kid, where ice is this kind of luxury in the tropics, to think about that. She would say: “You can make snowmen.” It was this very exotic memory that I wanted to figure out how to give life to again.

Also, on a very basic level, it was the body. An anthropomorphic reference, but anybody can do it. If I’m going to talk to the “everyday guy,” let’s use a form that they feel comfortable with. It’s primacy, I wanted to figure out how to engage with this primal nature. Then it was about using the material that it’s made of, to take it in different directions. For Mango Tourists, it’s made out of foam, and mango seeds, and capacitors and conductors, which are analog electrical parts. That piece was really about power, and the title—titles are really important to me. If you mined the title, it’s really talking about support, economic support, coming not from a local grid, but from a tourism grid. Power that’s not local, but coming from somewhere else. And the mango seed, I always thought the mango seed, when it dries up, looks like scrotum, this hairy sack. I always equated it with potentiality, this thing that is kind of dried up but also potential life. Then the electrical parts are all about this thing having all this potential and then in other ways being impotent. The weaving is about energizing the form. And it’s very present, that’s why I scaled it up, to make it very confrontational to the body. In the end, it’s just these things that get their power from you. The power is coming from your actualization—you’re physical engaging with them by looking at them more than them doing anything, and that part was about the notion of being a tourist.

Also, mango went to this idea, playing on a kind of Duchampian use of language, where it was also “man go.” So again, potentiality and movement. These things are just dormant, and they’re engaged with each other, but they can’t move themselves.

RAIL: Yeah, they have to be initiated through relation.

WARD: Right, and your imagination for them, more than anything else.

Nicole Smythe-Johnson is a writer and curator living in and working from Kingston, Jamaica.